Prologue

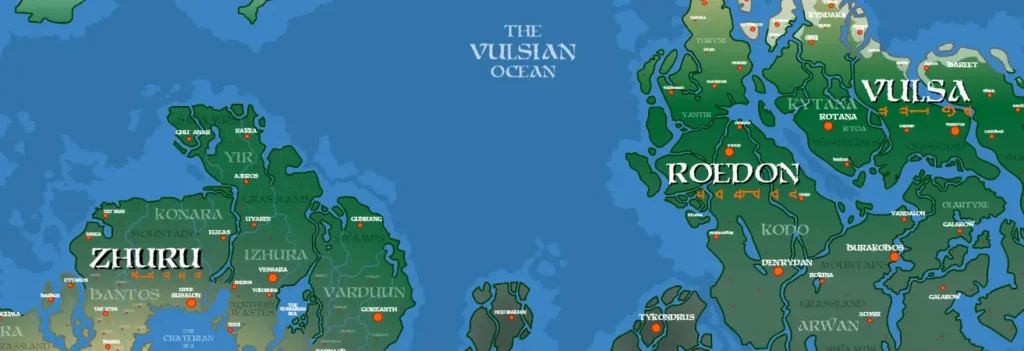

During the destructive and costly campaign through the northern Roedon territories, the imperial host of Zhuru came into direct conflict with the snow leopard peoples—native to the high valleys and glacier-fed passes.

These leopards, though scattered and loosely bound by clan and oath, proved more than capable of resisting the organized military formations of the empire. Blood was matched for blood. In time, the defenders not only held their ground but pressed back in key sectors.

Facing a grinding stalemate, Volko Khan—white wolf of the elder Zhurian dynasties—resorted to employing local mercenaries. Often drawn from exile bands or lowborn outlanders, these fighters were used with reckless cruelty, their lives spent cheaply to “catch and hold enemy arrows,” as one report noted. This policy, while expedient in theory, was strategically flawed. It fostered resentment, encouraged disorder, and betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of the cultures he sought to dominate. Wasteful. Arrogant. Shortsighted.

Volko was already a despot in his own homeland—reviled, politically cornered, and denied broader legitimacy by rival courts. He had not come to Roedon in conquest, but rather in voluntary exile, having fled the shifting alliances of Zhuru’s central provinces. His campaign was not a march of imperial expansion but an attempt to supplant peoples, to build a new order from the bones of the north.

And so the wolves of Vulsa—disciplined, fierce, and obedient—bled out under his banners. Not for home. Not for duty. But for the arrogance of a soured dynast drunk on exile and borrowed war…

…With one exception.

Tantos and Lozh, warrior-grey wolves of Vulsa, lay dying beneath the forest boughs.

Lozh writhed, still breathing—barely. His body had been nailed to the forest floor: arrows through his chest, neck, knee, and groin. He fought to stay calm. He did not want his master, still bleeding out nearby, to cross into Zarhanda hearing the wailing of a sniveling pupil. But still—he called out.

“Master…” Lozh spat blood. “We can’t lose. Not like this.”

No answer.

“Ka’s blood, this hurts!” he hissed.

Tantos didn’t speak. He was pinned to a tree by fewer arrows, but two were through the lungs, and one was deep in the heart. Every breath came wet.

Then he shifted—slow, painful—turning his bloodied muzzle toward the misty wood.

“Boy,” he growled through the rattle in his throat. “Where be your brother Thahn? Or have we lost him to rumor, too?”

Lozh whimpered. He looked around the clearing, dazed, breath shallow. “He’s… he’s not here.”

A long silence.

Then Tantos began to laugh. Grim. Dry. Cold with Vulsan knowing. The kind of laugh that has already seen the end and accepts it.

“Why are you laughing?” Lozh gasped. “Master—we’re dying.”

“Aye,” barked the old wolf, coughing blood down his chest. “But he lives.”

They died there, beneath the shadowed green of the Roedon woods.

Their hearts ceased.

Their lungs emptied.

But the great bird-serpent lord, Ka, god of death, it’s said, had to pause before collecting their lights—for their laughter echoed too long. It stayed in the trees, in the blood-soaked moss, in the arrows that still trembled in bark and bone.

And far from that place, a third figure ran north. Not with fear. But with guile, and vengeance, and a mind already stripped of all civilization or barbarism. A wolf with nothing left to lose—except the chance to do something audacious. Something ruefully transgressive to the thrones of the Western Highlands.

The fortress of Dengan loomed high in the forested crags where the steppe gave way to the broken coast. Perched between frost-slick ridgelines and groves of old bamboo, it squatted like a wolf at rest—timbered jaws wide, torchlight flickering in its teeth. Walls of dark pine and charred stone formed its spine. Arrow slits glowed. Smoke curled from the chimneys of the great hall.

Within, the daughter of Volko Khan moved like an ornament between rooms. White silk. Thin anklets. Surrounded by guards. Her laughter was light but hollow, guarded by six in each wing, all of them nervous from the morning’s slaughter. They whispered of ghosts. Of vengeance. Of a grey bastard with white hair.

The banners above the main tower barely moved. The frost had frozen them stiff.

From above, one could trace the keep’s order: the outer garden with its knotwood trails, the maproom near the east flank, the hollowed belly of the assembly hall, the narrow armory tucked beside it. Then the training ring, strewn with hay and broken shields. The meadhall, still lit from below. A private chamber beyond. And near the far corner—almost hidden from the inner court—a side door, half-covered by a fallen lintel beam.

That door shook.

A guard braced against the side door, breath fogging the timber, both arms straining to keep the hinges shut. He could not scream. A knife had already punched into his throat. A wet, gargled plea leaked from him as the blade drew back, then drove in again—opening him from shoulder to jaw. Blood spattered the lintel. His body slid down the frame.

Something massive pressed through the gap: a grey-furred arm, slick with ash and blood. The hand clamped around another guard’s neck before he could draw. Bones cracked. The smaller wolf’s eyes bulged; he clawed at the wrist, snapping his own fingers against the iron grip.

Two more guards came running—one shouting as he stabbed at the invader’s arm. His dagger found purchase once, sank into the forearm, and twisted—but the arm did not release. It only tightened. The sound that followed was wet and final.

Then came the sword.

It didn’t merely breach the door—it split it. The broadsword punched through the upper planks, through the lock, through the ribcage of the third guard in a single violent shove. The blade withdrew with a howl of tearing wood, then swept down—shearing the handle, bolt, and hinge clean off before the door itself caved inward. A splintered shard caught one wolf across the eye; he went down shrieking, pawing at his face. The other slipped in his own blood and fell back, tail curling under him in terror.

A Massive grey wolf entered. White haired, amber-eyed, fangs gleaming white.

The Vulsun’s massive shadow filled the doorway, shoulders heaving, breath steaming in ragged bursts. His eyes caught the firelight like hellfire imprisoned in a dark and rueful forge. He stepped over the crawling guard, yanked his knife from the corpse’s flank, and without slowing, crushed the survivor’s skull beneath his heel. Bone gave way with a muted pop.

The body twitched once, then stilled.

The chamber reeked of pine smoke and blood. Somewhere deeper in the keep, a voice cried alarm.

The Vulsun slayer rolled his shoulders, flicked the gore from his sword, and moved on.

He did not halt.

Two more surged from the shadows, blades drawn. The first overextended; the figure moved like smoke, slashing once—clean at the elbow—and caught the falling sword mid-air. The second had time to shout. The Grey slayer turned not on him, but on the brazier.

One swing.

Ash exploded in the guard’s face. Fire bloomed in his beard and hair. He screamed as he stumbled backward and fell over the balcony rail, vanishing in a hiss of flame and bone.

The others rushed him.

“Where is your Khan?” the Vulsun snarled, voice dry as bark. Steel flashed. Another guard burst through the side door and took a sword to the gut before he could speak. Then silence.

Stepping over the bodies, he began to climb.

The upper paths were narrower, ringed with lattice railings and brittle ivy. He moved quickly now—up toward the raised garden—but two more stood in his way: a grey wolf, young and keen-eyed, and a Londorian brute with heavy shoulders and brown pelt. Both trained. Both armed.

The three met in a flurry of sparks. Steel rang. The grey wolf struck low. The Invader parried, turned him with a shove—straight into the Londorian’s rising thrust. The brown wolf faltered. Too slow. The Vulsan twisted the blade from his hands, drove it up beneath his chin, and left him twitching against the wall.

Now seen in full light, the intruding Vulsan slayer’s fur was thick with gore. His chest rose like a bellows. His eyes took in the keep like prey yet to be bled.

He kicked in the next door. A guard sat playing cards. His head came off before he could look up. Another at the table rose to draw. Too late. The gut spilled hot across the board. Dice clattered in blood. The Grey-wolf slayer took the larger blade from the second one’s corpse. A heavier sword—lion-forged, still warm from use. He slid the new dagger into his belt.

The next door shattered. Inside, a snow leopard slave girl lay gasping beneath a mounted guard, her face turned from the wall, legs pinned. She whimpered. Her arms bore bruises. Neck rings. Gold bangles. The male looked back—snarling.

The feral grip of the Vulsun slayer pulled him off mid-thrust, jammed his own sword through the bastard’s mouth, and nailed his skull to the back of the chamber door. The leopard stared in shock as the blood ran. She sat up, naked, shivering, fur matted, paint smeared from her cheeks. When The Slayer stepped forward, she flinched.

He raised his sword—then knelt. One stroke. The chain fell free from her collar. He opened the door and held it. For a long moment, she didn’t move. Then she looked into his face. Saw what had been done. Saw the bodies. She gasped, once. Nodded. Then ran barefoot down the corridor. As she vanished, she pointed—up the stair—and her eyes thanked him.

The slayer climbed. The top floor was quiet. A corridor of red paper lamps and polished wood. No guards. No sound.

He kicked the final door wide. The Khan’s daughter sat inside. Not Frightened. Not hiding.

She looked up—and lit with a mischievous joy. She crossed the chamber in three steps, silk fluttering behind her. She didn’t ask How he had escaped. She didn’t ask what had happened outside. She kissed him. He did not kiss back.

But she growled—a low, wicked thing—and ran her hand up his chest. Her fingers found his bulge beneath the blood-wet sash. She bit her lip. Moaned, just barely.

No words passed.

None were needed.

The hooves of ten steeds thundered across the wide steppe, a storm of dust and fury beneath the blood-red sun.

At their head rode Volko Khan, lord of the horselands, his teeth clenched around a curse, sword bare and gleaming in the dusk. His face, scarred and cruel, was more wolf than male, and his left eye—seared milky by an old wound—blazed with a sick, unholy fire.

His mouth dripped red where the young bastard they now pursued had struck him, splitting lip and tooth alike. That wild-born grey dog. Volko spat blood and loosed a roar that made his own line recoil—horses shying, riders stiffening. Behind him, his nine sworn riders bent low in their saddles—black shapes who feared their master more than death itself.

They had been scouring the wastes since morning, chasing shadows across the dying grasslands. The trail belonged to one who should have died with his kind. For Volko had loosed the northern dogs—those grey-furred mercenaries, bred in cold and famine—to butcher his enemies. And butcher they did: cut down to the last, their carcasses left to rot beneath the sun.

But one had not fallen.

One had survived.

And worse than survival—he had laid hands upon the Khan’s own blood.

Now, cresting the rise, they beheld a sight that drove Volko to bellowing madness.

Against the flaming disc of the sinking sun stood a lone figure—a grey-furred wolf, his mane of long white hair streaming in the wind. His chest heaved with the savage joy of a battle lived through. His laughter carried like a war-drum beat.

Before him sprawled the Khan’s daughter. Her slender frame trembled, silks in tatters, her maiden’s flush betrayed by the sweat upon her thighs. His haunches pounded into her. Mocking. Ejaculating. Usurping.

Even as the Khan’s roar split the heavens, the wolf pulled free with a wet, vulgar pop, slapping her round haunch with a barbarous hand. She arched beneath him, lips parted not in terror—but in the swoon of awakening.

He had spilled seed into her womb. The wet gleam of his doing mocked her father’s rage.

The mercenaries had died at arrow-flight behind him. A hundred corpses still bled into the dust. Yet this nameless wolf—this bastard survivor—had seized from the world a prize none had dared dream.

Volko’s riders shrieked and spurred. Their mounts foamed.

But the wolf only laughed louder.

His balls swung as he ran, slapping against his thigh, leggings half-drawn with a mocking grin. His strength undiminished. His spirit ablaze.

Spurred on by confidence only granted to one who is alive when all others lie dead.

The wolf-lord’s daughter swooned, even as her father stood over her—aghast. The white sheen dripping from her thighs shamed him more than any blade ever could.

Without a word, without a glance, she mounted the spare horse they had brought. Its ivory tack caught the dying sun.

Volko stood frozen. Shaken. Beyond rage—but impotent.

He watched his riders stumble, trample, and fail—utterly fail—to reach the grey bastard son of a whore before he vanished into the dark line of forest shadow.

The Roedon Blackwoods swallowed him whole.

A moment passed.

Then another.

The Khan’s men looked to their lord, terrified—for his gaze was a blade that cut flesh from bone.

Then—from the treeline—a final insult. Not laughter. Not the howl of triumph.

But words.

The bastard dared speak:

“Let this be the last time you underestimate Thahn of Vulsa… you most regal and noble son-of-a-bitch.”

Then came the laughter. Deep. Resonant. As if the forest itself laughed with him—concealing him, honoring him, birthing him into legend.

Volko stood red-faced, lip split, helmet flung to the dust. He howled—a bloody, primal wail that sent crows shrieking from the sky.

And behind him, his favorite wife’s daughter—her body still raw from the wolf’s touch—smirked from her saddle, cheeks pink with the memory of conquest.

And so it was that Volko Khan’s realm ceased to be his own—not by siege, nor treaty, but by failure of measure. In seeking to dominate the northern reaches, he had failed to recognize the quiet erosion of power from within. By the time his riders reached the coast, the damage was done.

This bastard, rogue of the north that he was had shattered more than discipline. He had broken deals, undone alliances, and left the once-feared wolf-lord disgraced. The promised virgin, meant for the princely dowry of a key ally, had been defiled. Worse, she had not been taken—she had gone. Of her own will.

Among the dead left strewn across the keep were not only guards and gatemen, but the core of Volko’s inner circle. His vizier Yipan, his alchemist Vuzhul, his spymaster Zalfathang—all silenced.

Of the guards who lay among them, Many were found in compromising death: cocks wet, dice still in hand, throats open. A quiet shame.

By the time Volko turned back toward his seat, the fortress of Dengan had become a ruin. Its gates left ajar. The black mountains whispered. Roedon watched. And all knew that he had been undone not by horde, nor empire,

but by a single grey Rogue who now ran free.

Next Time

With blood on his hands and water up to his neck, Thahn escapes the grim, dark coasts of Vulsa, only to run afoul of bloodthirsty coursairs on the high seas.

More

The Chronicles Of Thahn

COMING SOON

- Black Sail From Vulsa

- Hounds Blood