Over the past few weeks you’ve probably noticed real, visible changes across the site and the wider HTH Studios ecosystem, and that’s not accidental.

New structures are going up, old ones are being reinforced, and some long-gestating ideas are finally being treated as first-class projects instead of ghosts from ten years ago.

Some have complained that it’s unprofessional to expand into new work while High Tail Hall isn’t “finished.” That criticism collapses the moment you stop pretending “finished” is a meaningful word in game development. People played it ten years ago. They’re still playing it now. They’re still talking about it, and they’re still waiting for its return. By any honest standard, something was completed—and its continued life proves it.

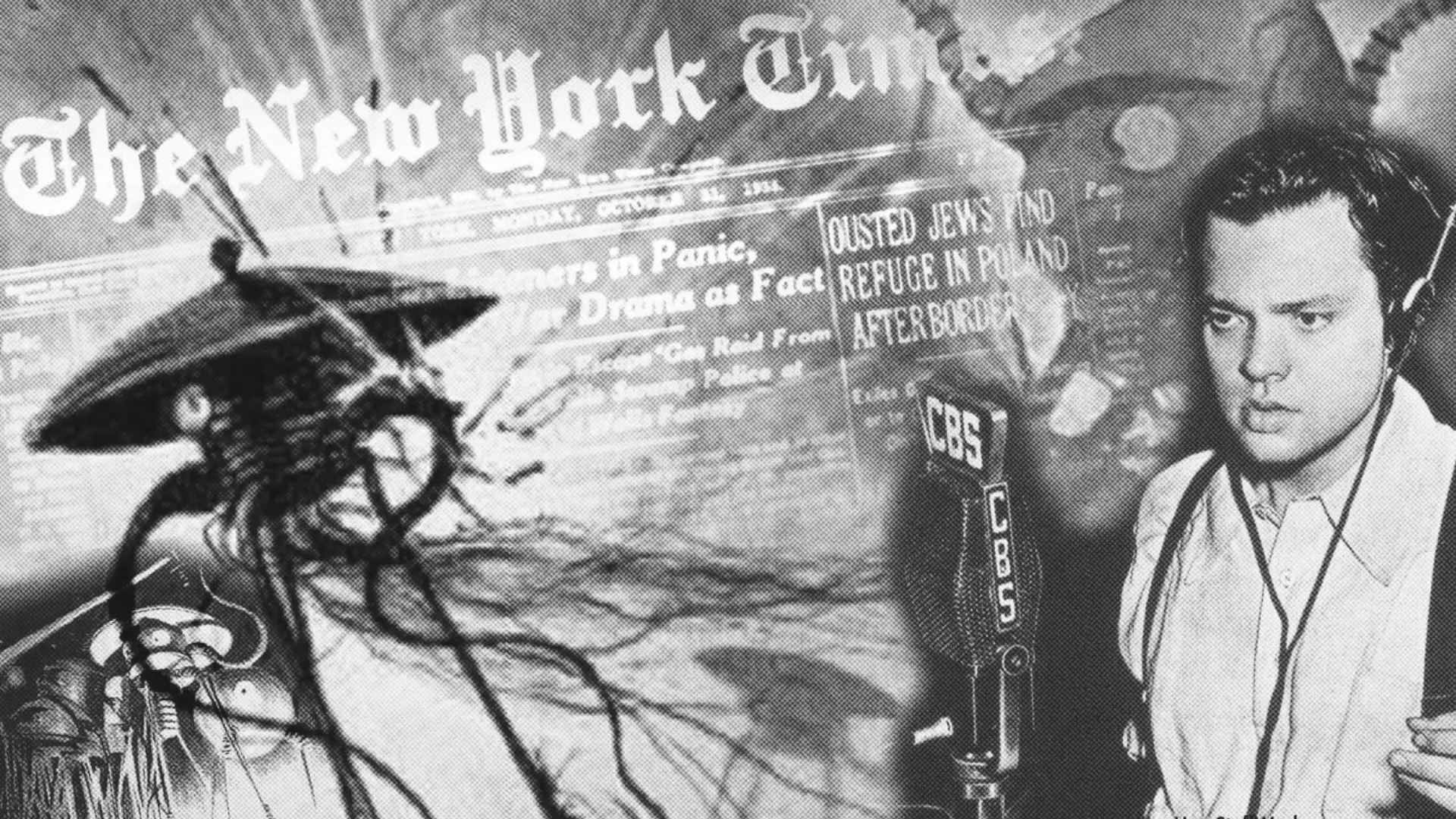

So why the focus on Primal Sword & Sorcery? Because it isn’t a side imprint or a vanity project. It’s a deliberate response to a cultural vacuum. Myth has been hollowed out across mainstream media. Star Wars, Star Trek, the MCU—whether you once loved them or not—isn’t coming back to a mythic state. There’s no triage plan that restores that spark.

Those systems are done, and what’s left is maintenance and messaging.

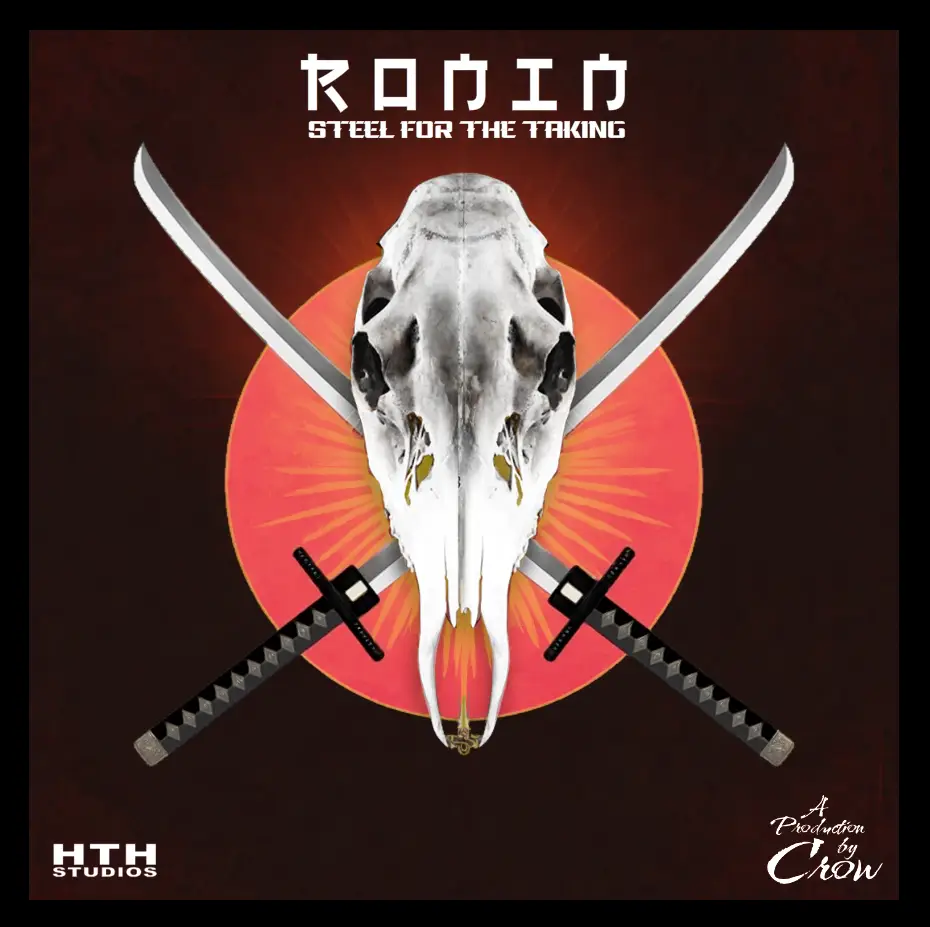

That vacuum is where the interesting work happens. For thirty years, there has been money, fandom, and demand for real, “Anthro”, sword and sorcery—violent, erotic, mythic, heavy-metal, bloody, filmed like film, not sanitized, not ironic, not embarrassed of itself. And somehow, despite all that time and all that capital, it never happened.

Not once.

Today, with modern tools, that excuse is gone. We can do things that would have required massive budgets, brutal compromises, or outright impossibilities decades ago—and we can do them without killing stuntmen in the process.

Primal Sword & Sorcery exists because nothing is stopping us anymore.

This also isn’t about hoarding IP or building a walled garden. I’m setting aside infrastructure and legal space so this work isn’t just mine. I’m a capitalist; I believe in people making money. I like the idea of my audience having real, disposable income, building their own myths, and profiting from them.

Not fanfiction. Not unpaid labor. Real work, sold legally, in the open.

If that sounds unconventional, good—it’s supposed to be.

I’ve been building worlds my entire life. I don’t struggle to invent civilizations, timelines, or mythic systems; I do it reflexively. The Vandyrian Empire is one of those systems—and it isn’t even the biggest or the most interesting. Infinite Sky, Structure One, and what comes after will be treated the same way: codified, documented, and made usable by others. These codices aren’t collectibles. They’re tools.

And no, this isn’t about chasing billionaire fantasies. Yacht money is a joke. Owning a yacht means owning a crew and a logistical nightmare. If you want the experience, you rent the damn thing and walk away. What actually matters is good entertainment that isn’t filtered through corporate cowardice or ideological scolding.

We’ve seen what happens when myth is locked behind corporate gates. We’ve watched Star Wars, Trek, Conan, D&D—all of them—become vehicles for control, dilution, and lectures instead of inspiration. I’m not interested in repeating that experiment.

If that means handing the fire to others and letting them build, burn, and profit with it, so be it. The tools exist.

The space exists.

The culture is starving for it. Have at it.

The Greater Vandyrian Empire is Yours.

and hell, did I not promise you that “Free content would be coming back in a big, big way.”?

![M8TINGS [SINGLE]](https://hthstudios.com/website/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Page.M8TINGS.webp)